Geral

The Economist

WHEN Swedes voted in 2003 on whether or not to join the euro, most political and business leaders were strongly in favour. Today even the euro’s supporters are grateful to the 56% of voters who said no. As worried investors push up yields on government bonds right across the euro zone, yields on Swedish ten-year bonds have fallen to 1.7%, more than half a point below German Bunds.

Anders Borg, the finance minister, still thinks that in the long run Sweden should join the euro. But he seems happy to be out for now. Fears that Sweden, a small export-based economy, might suffer if it kept the krona were a strong pro-euro argument in 2003. Yet Mr Borg says that Sweden has gained something from standing aside. “Being an outsider, you must make sure your competitiveness and public finances are in order. We have had to impose on ourselves a self-discipline that euro countries did not feel they needed. If you know the winter will be very cold, you have to ensure the house has been built well. Otherwise you will freeze.”

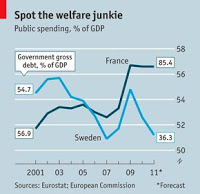

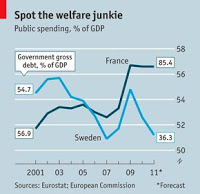

In Sweden this translates into tight fiscal policy, a budget surplus of some 0.1% of GDP and a shrinking public debt. With memories still fresh of the banking and housing bust in the early 1990s, all political parties accept the need for sound public finances. Exports fell after the financial crisis in 2008 but have bounced back, helped by a weaker krona. Last year GDP expanded by 5.7%. This year it may grow by another 4.4%; third-quarter figures were better than expected. Yet Sweden will be hurt by the euro zone’s troubles. Exports make up half of GDP and many companies report slowing foreign demand. Growth could drop below 1% next year.

The centre-right government plans to impose stricter capital rules on Sweden’s four big banks (Handelsbanken, Nordea, SEB and Swedbank) than elsewhere. The finance ministry wants to see tier one capital worth 12% of risk-weighted assets by 2015, five points above the Basel minimum. The aim is to avert any chance of Swedish taxpayers again paying for “irresponsible risk-taking”.

Mr Borg often urges fiscal prudence on his European colleagues. Sweden has given emergency loans to Ireland, Latvia and Iceland as they, according to Mr Borg, have shown a credible ambition to clean up their economic mess. He is less forgiving of Italy and Greece, saying they need to do much more. It is a pity that Sweden is too small to make much impact on the wider European economy—and that Mr Borg has so often found himself preaching to the deaf.

- How The Euro Will End

By GERALD P. O'DRISCOLL JR, WSJ The euro is the world's first currency invented out of whole cloth. It is a currency without a country. The European Union is not a federal state, like the United States, but an agglomeration of sovereign states....

- Here We Go Again

Buttonwood, The Economist THE pattern is eerily familiar. Investors start the year in a blaze of optimism, hoping that the euro zone has been stabilised and that the American economy is growing strongly. By the late spring, the latest example of euro-zone...

- Eurozone Is Starting To Look Japanese

By Richard Milne, Financial Times Amid the topsy-turvy nature of markets in recent weeks, one extraordinary event almost went unmarked. Short-term German interest rates, represented by two-year bond yields, fell below their Japanese equivalents last week...

- An Exit Strategy From The Euro

By ROBERT BARRO, WSJ Until recently, the euro seemed destined to encompass all of Europe. No longer. None of the remaining outsider European countries seems likely to embrace the common currency. Seven Eastern European countries that recently joined...

- Blame It On Berlin

Editorial do WSJ The euro bailout caucus wants the Germans to write a blank check. Which century is this anyway? We ask because elite opinion is once again blaming Germany for ruining the rest of Europe, if not the entire world economy. All that's...

Geral

Sweden and the euro: Out and happy

The Economist

WHEN Swedes voted in 2003 on whether or not to join the euro, most political and business leaders were strongly in favour. Today even the euro’s supporters are grateful to the 56% of voters who said no. As worried investors push up yields on government bonds right across the euro zone, yields on Swedish ten-year bonds have fallen to 1.7%, more than half a point below German Bunds.

Anders Borg, the finance minister, still thinks that in the long run Sweden should join the euro. But he seems happy to be out for now. Fears that Sweden, a small export-based economy, might suffer if it kept the krona were a strong pro-euro argument in 2003. Yet Mr Borg says that Sweden has gained something from standing aside. “Being an outsider, you must make sure your competitiveness and public finances are in order. We have had to impose on ourselves a self-discipline that euro countries did not feel they needed. If you know the winter will be very cold, you have to ensure the house has been built well. Otherwise you will freeze.”

In Sweden this translates into tight fiscal policy, a budget surplus of some 0.1% of GDP and a shrinking public debt. With memories still fresh of the banking and housing bust in the early 1990s, all political parties accept the need for sound public finances. Exports fell after the financial crisis in 2008 but have bounced back, helped by a weaker krona. Last year GDP expanded by 5.7%. This year it may grow by another 4.4%; third-quarter figures were better than expected. Yet Sweden will be hurt by the euro zone’s troubles. Exports make up half of GDP and many companies report slowing foreign demand. Growth could drop below 1% next year.

The centre-right government plans to impose stricter capital rules on Sweden’s four big banks (Handelsbanken, Nordea, SEB and Swedbank) than elsewhere. The finance ministry wants to see tier one capital worth 12% of risk-weighted assets by 2015, five points above the Basel minimum. The aim is to avert any chance of Swedish taxpayers again paying for “irresponsible risk-taking”.

Mr Borg often urges fiscal prudence on his European colleagues. Sweden has given emergency loans to Ireland, Latvia and Iceland as they, according to Mr Borg, have shown a credible ambition to clean up their economic mess. He is less forgiving of Italy and Greece, saying they need to do much more. It is a pity that Sweden is too small to make much impact on the wider European economy—and that Mr Borg has so often found himself preaching to the deaf.

- How The Euro Will End

By GERALD P. O'DRISCOLL JR, WSJ The euro is the world's first currency invented out of whole cloth. It is a currency without a country. The European Union is not a federal state, like the United States, but an agglomeration of sovereign states....

- Here We Go Again

Buttonwood, The Economist THE pattern is eerily familiar. Investors start the year in a blaze of optimism, hoping that the euro zone has been stabilised and that the American economy is growing strongly. By the late spring, the latest example of euro-zone...

- Eurozone Is Starting To Look Japanese

By Richard Milne, Financial Times Amid the topsy-turvy nature of markets in recent weeks, one extraordinary event almost went unmarked. Short-term German interest rates, represented by two-year bond yields, fell below their Japanese equivalents last week...

- An Exit Strategy From The Euro

By ROBERT BARRO, WSJ Until recently, the euro seemed destined to encompass all of Europe. No longer. None of the remaining outsider European countries seems likely to embrace the common currency. Seven Eastern European countries that recently joined...

- Blame It On Berlin

Editorial do WSJ The euro bailout caucus wants the Germans to write a blank check. Which century is this anyway? We ask because elite opinion is once again blaming Germany for ruining the rest of Europe, if not the entire world economy. All that's...